ART WORLD NEWS

Martin Wong and Aaron Gilbert’s Social Realism is Local and Cosmic – ARTnews.com

On my way to P·P·O·W’s new storefront gallery in Chinatown, coming out of the Canal Street J/Z subway, I walked past an imposing gray building that I later learned was the Manhattan Detention Complex. Known as “The Tombs,” it housed several hundred inmates before closing in November 2020. Turning off Walker Street, I passed a crowd waiting in front of the New York City Rescue Mission on Lafayette, and a woman asked if I could buy her lunch. I turned the corner on Broadway and walked into the gallery.

“1981–2021” was a robust two-person show featuring the paintings of late Chinese-American artist Martin Wong and Brooklyn-based artist Aaron Gilbert. Many of their subjects—people enmeshed in the incarceration system, experiencing homelessness, or in a position of economic precarity—could be denizens of the Lower East Side. The challenge of this show, of viewing it in context, was to think about the relationships between the images inside the gallery and their referents, who, at times, were right outside. Could those relationships inspire anything other than awareness or pity?

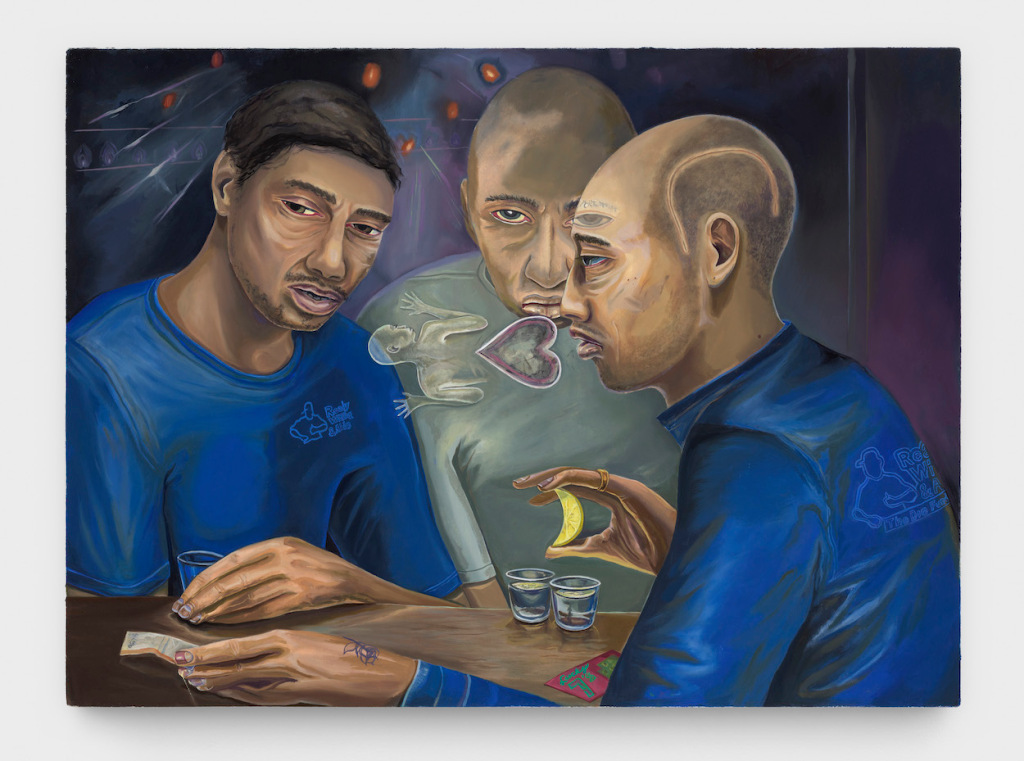

The first thing I noticed in Gilbert’s portraits was the way he paints eyes—rimmed in yellows and purples and blues, flattened and enlarged, almost reptilian. They evince an existential, almost cosmic exhaustion. In Ready Willing and Able (2020)—one of two paintings hung in the gallery’s front window—three men, presumably workers for the transitional labor and housing program referenced in the title, confer at a bar. Two of them look furtively to the left, while the other looks directly out of the painting, a ghostly outline of his left eye bleeding through his friend’s intervening head in profile, as if a stare could penetrate flesh.

Martin Wong, Everything Must Go, 1983, acrylic on canvas with hand-painted frame, 48 by 60 inches.

Courtesy the Estate of Martin Wong and P·P·O·W

In one particularly striking combination, Gilbert’s Empire State of Mind/Flaco 730 Broadway (2020) is paired with one of Wong’s most famous paintings, Everything Must Go (1983). The hanging emphasizes the artists’ shared motivators (grief, social documentation) as well as the differences in their approaches. Gilbert focuses on intimate scenes; Empire depicts two figures, seemingly mother and son, grieving in the street, perhaps from the effects of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Wong is more interested in the cosmic, architectural, and environmental; Everything juxtaposes the debris of a demolished Lower East Side building with a night sky constellation, gold-painted hands spelling out the work’s title in ASL, a rainbow gradient that may allude to the HIV/AIDS epidemic, and a trompe l’oeil frame painted in deliberate, bento-box-like sections. Wong’s mysticism seems like a balm for Gilbert’s specific human dramas. The two canvases also illuminate each other’s historical and temporal scales, connecting two social and biological crises across time. And while the immense scale of Wong’s image-world does not lead the artist to neglect the minute—broken bricks stand in for societal conditions—Gilbert’s portraits use details to index the reality of a person or a larger narrative. The fallen health insurance card in Goddess Walks Among Us Now (2020), the parking ticket and energy bill tacked on the fridge in Love Still Good (2021), and the card on the dashboard of Summons (2020) depicting Babalú Ayé, the Yoruba spirit of healing, help render the lives of countless people subjected to forms of economic precarity, all of them glowing in fluorescent hues. His attention imbues these lives with all the symbolism and heft of a Renaissance painting.

While Gilbert’s paintings draw us into social dramas, Wong’s paintings often present literal barriers to accessing his subjects. Lock-Up (1985), a canvas nearly life-size, looks into a prison cell where an inmate sleeps on a cot. Viewers encounter this scene through the thick bars of the cell, rendered in crumbly acrylic paint, partially blocking our view. In Cell Door Slot (1986), an inmate peers through a slit in a metal door, and the narrow canvas itself seems to imprison its subject.

Wong’s homosexuality is not a key part of the conversation between his and Gilbert’s work, but love, connection, and family are depicted in both artists’ paintings. Peek at the embrace of the little couple at the bottom of Wong’s Sharp & Dottie (1984), or the warmth of Gilbert’s Love Still Good, where a child floats in balletic suspension between her caretakers. Wong and Gilbert show an inspiring degree of care in rendering their subjects, who, as one is reminded on exit, are not dissimilar from those waiting on the street outside the shiny white gallery. More than prompting awareness or pity, these paintings ask us to invest the same care in the issues of incarceration and homelessness right outside the door.